Two hours is exceptionally short.

Oh, the internet has trained you to think it’s long and arduous, but it’s not. It’s nothing.

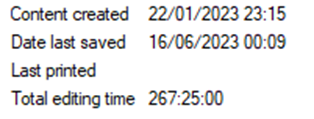

The best proxy I have for the amount of time I spent directly working on the video above comes from file explorer’s record of how long the script was open on my PC.

267 hours covers the entire script writing process, all the recording, and some of the video editing (I mostly had it open alongside my video editor, sometimes didn’t). That comes to two hours per minute of finished video. 120 videos per video. This is likely a significant underestimate though, since it doesn’t include times I edited the video without the script alongside me, it doesn’t include the survey analysis, and it doesn’t include the research.

So yeah, I can’t piece together a reliable estimate for everything, but I spent a lot of time on this.

Compared to all the other effort expended in the mass extinction debates though, it’s downright atomic. Half a year of one person’s free time – no matter how many weekends they spent moving silly animations around instead of being a functional human – isn’t a research career. I am nowhere near an expert.

Now the video is done and I can finally get on with the rest of my life, I thought it would be nice to finish with an article about what I couldn’t fit in the two hours I ended up with. Not everything of course. Not even close. This article will likely be much shorter than the video script. But it will cover things at a slower pace without the demands of tightly-written mass-consumable entertainment, filling in some gaps and recontextualising a few creative decisions.

It will be part production diary, part expansion of the content, and part meta-analysis (because the video wasn’t meta enough as it was). More than anything though, it’s haphazard closure for myself to mark this project as done.

It’s going to be full of even more rambling and navel-gazing than the video, so if those aspects annoyed you, turn back now.

Production

As covered in the video, my journey began with a single quote lifted from the Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology about media’s involvement in the mass extinction debates. My video’s crazy wall is accurate – I wanted to make another video in the style of Jefferson’s Mammoth Cheese because that was so fun, and backtracked my way through an old project to this half-remembered line.

Around one-third of the scholars involved in the debate on the connection between mass extinction of dinosaurs and a meteor collision with the Earth – another controversy with broad public resonance – stated that they had heard of the impact hypothesis from the mass media.

Massimiano Bucchi

A great irony in all this, by the way (which I only noticed after the video was basically done), is that this quote actually gets the original claim slightly wrong.

Midway through the 1980s, one survey found that almost 30 percent of a sample of palaeontologists in five countries first read of the Alvarez hypothesis in “scientific commentaries” rather than in journal articles.

Elisabeth S. Clemens

‘Almost 30 percent’ becomes ‘around one-third’, ‘palaeontologists’ becomes ‘scholars’, and ‘scientific commentaries’ becomes ‘mass media’. Subtle but intriguing changes, especially considering the emphasis on communication across different fields.

My original intention was a ten-minute video about science communication models, using the mass extinction debates as an overarching but ultimately thin case study for the continuum model. This section still survives in spirit in the second half of Part IV.

When I went hunting for a tiny bit more detail, I traced the quote’s source to The Mass-Extinction Debates, edited by William Glen. Note the hyphen in his version and the lack of hyphen in mine. I took the hyphen out because that makes it a pun (mass extinction or mass debates?). I suspect he kept the hyphen in to make sure it wouldn’t be interpreted as one. To make the point again: he’s a scientist, and I’m not.

I knew straight away this couldn’t remain a short video, so I put it on the backburner for a while as I wondered what to do with it.

There are several YouTube creations I came across in the intervening time that had a strong influence on my evolving vision:

- America’s Missing Collider, a series by BobbyBroccoli. Knowing that extensive overviews of intricate science history – complete with great pacing, stunning visuals and the odd dash of humour – could be made for YouTube by a single person convinced me to do the same. So thanks BobbyBroccoli, for making me believe I could make a full-on documentary, and for making me not-quite-but-very-nearly bite off more than I could chew.

- ROBLOX_OFF.mp3 by hbomberguy. Madness of the most brilliant kind. Taking a global icon, deconstructing its origins in growing fits of insanity, and coming to an unexpected yet entirely inevitable conclusion about a wider societal phenomenon. Wonder where I got that idea…

- The Undebunkable by Captain Disillusion (along with many of his other videos). What is real? What is fake? How much scepticism is the correct amount, especially in the age of YouTube? How did I take so long to discover this man?

- Dino Docs Ranked, a series by Red Raptor Writes. Impressively well-researched analyses of documentaries that were largely responsible for getting me thinking about dinosaurs and dinosaur media again after a spell outside that sphere.

I began research in earnest in early January once other projects were out of the way. Some sources were books I’d read before, others new, and supplemented by a healthy dose of journal and news pieces across the academic-popular continuum. All can be found in my credits list. The sources for this blog post are the same.

My research notes run to 26,000 words, not including a lot I didn’t write down explicitly. For instance, I devoured two entire books so quickly that I couldn’t be bothered to keep pausing to make notes, relying instead on a purely mental reference list. I did re-check everything from the books themselves when I wrote the script, but it’s still hilarious to me to have only the following actually written for both.

For comparison, the video’s script is only 19,000 words, and that’s full of jokes, asides, and general boilerplate. I had to read and watch a lot to cover everything I did, and again, that’s a drop in the ocean.

I missed the delivery of The Mass-Extinction Debates itself and had to collect it from the post office before work the next morning. Hard to imagine now in July, but it was a frigid and icy January day. I slipped over twice on my way across town, sustaining minor injuries. Honestly, the lengths I go to for you people.

Three sources more than any others had a major impact on the script’s direction:

- The Mass-Extinction Debates (obviously). You might ask why I didn’t contact William Glen directly for more research given the prominence of his work in my video. Anxiety is surely a large part of the reason I didn’t, but from a practical standpoint, he’s 91, long-retired, and may not even know what YouTube is. I thought it better not to bother him.

- When Life Nearly Died by Michael J. Benton. While it’s actually about another extinction (the Permian-Triassic extinction, when 95% of marine species on Earth disappeared in the planet’s greatest ever crisis) it proved an incredible account of the history of geology and palaeontology. Part II wouldn’t exist without it.

- A news article about a recent “breakthrough” discovery about volcanism that…you know what, I’m going to need a few more paragraphs for this.

I won’t name the article or its subject. The intrepid amongst you will find it in my sources, but I’d like to keep my connections to it minimal because it disappointed me.

William Glen mentions in his interview with LearningStewards that he has to be careful when discussing the lives and opinions of living people. Publicly discussing science of the past is one thing, but naming and judging those involved in modern controversies is a much more uncomfortable endeavour.

I made a point to follow this advice. Every living scientist I mention by name in my video comes across positively because I do genuinely view them positively. But when discussing the grittier back and forth of the debates since 1980, I made everyone a faceless caricature on purpose.

The article I’m referring to purports to be an account of the K-Pg tussle, but coming at it from the perspective of someone who’d read The Mass-Extinction Debates – a book compiled by a man whose life’s work has been studying them – I was, frankly, outraged. It engaged in rampant historical revisionism, substituted academic rigour with character profiles, and claimed volcanist mavericks were shunned by the media without a hint of irony.

To quote my own research notes:

I have an entire book next to me arguing that this was a massive debate for years and this article blithely claims the thing was settled immediately just to paint [REDACTED] as a maverick. I’m never believing anything I read in [REDACTED] again.

Me

You know what the real problem was though? The internet’s reaction to the article.

I found tweets and posts from anti-vaxxers and climate change deniers salivating over this example of a “broken” paradigm and the ostracised individuals fighting against it. If such a fundamental fact – an asteroid killed the dinosaurs – is being upheld by deceit and conspiracy, what about climate change? What about vaccines? Scientists are all corrupt and know nothing!

Suddenly I was seeing the same phenomenon everywhere. While searching for K-Pg maps to use for my animations, I found the incredible work of Christopher Scotese, who, legend that he is, granted me permission to use his plate tectonics animations in my video. I also found Facebook posts featuring these same plate tectonics animations. I should have turned back, but I looked at the comments: a dystopian hellscape of rage at the scientists who must be lying and making stuff up for kicks.

And this was geology! Ordinary people were getting this riled up about dirt!

(Not trying to insult geologists, it’s just not the sort of thing laypeople tend to care about.)

My motivation for the whole video became a desire to inoculate people against this sort of sloppy journalism. I knew then what my conclusion couldn’t be. It couldn’t be an uncritical dismissal of paradigms simply because they’re paradigms. As for what the conclusion would be…well, we’ll get there.

Research, travelling to locations featured in the video, script-writing, and running the survey overlapped throughout January and February as things came together.

I’m quite proud of my survey. I still can’t find any hint of proper surveys of public belief about the extinction of the dinosaurs (cough, not you, Daily Mirror, cough). In truth I didn’t look too hard, so maybe they exist, but I do think my data is potentially valuable as part of the modern debates. Not wholly scientific, but as a casual decentralised thing, it’s neat.

I’ve published the raw data from my survey by the way, in case you’d like to see the other entertaining answers that didn’t make it into the video. There are many. You can also find the full-detail pie charts for Q1 and Q2 here and here respectively.

On-location filming was another novel development as far as my videos go. Let’s just say I have much to learn…thank God for video stabilisation.

If you look closely, you’ll notice everyone in the footage from the Natural History Museum and Crystal Palace Dinosaurs is wearing winter clothes, another marker of how long I spent with this video dominating my free time. Sure, they were nice trips, but I wish I’d had the chance to enjoy them without the need to capture everything for #content. Crystal Palace Park in particular was lovely, a surprisingly peaceful little treat filled with historical reverence. The same couldn’t be said of the actual journey there and back, a mess of trains even more packed than usual.

And yes, I really was briefly stranded in Swindon due to flooding-induced train chaos on the way back from the Natural History Museum, and I really did catch COVID-19 during my trip to Crystal Palace. I blame Great Western Railway on both counts.

With primary and secondary research collected and some first-hand footage to spark inspiration, I started pulling together a script.

The intro sprang forth effortlessly before I’d done most of the research and had a strong bearing on my priorities moving forward. Many of my videos happen like that: I write the intro to solidify my mission statement, then I act on it.

Using the history of the ‘dinosaurs’ vs ‘non-avian dinosaurs’ clarification as a rushed microcosm for scientific dynamics is, I have to be honest, something I’m immensely proud of. Despite knowing that birds are dinosaurs, I didn’t know the exact reason until I made this video. I knew they evolved from dinosaurs, but few science communicators I recall have ever stopped to explain why ‘non-avian dinosaurs’ as a term exists in scientific nomenclature. Why do scientists bother with it?

If you don’t provide that context, the public come away feeling needlessly segregated. ‘Birds are dinosaurs’ is, in my opinion, the perfect example of Goldacre’s ‘groundless, incomprehensible, didactic truth statements’. Now it pains me every time I see someone berating non-scientists for using ‘dinosaur’ to mean ‘non-avian dinosaur’ without considering the different contexts and the reasons science and the public have created different perspectives. I explained phylogenetic classification and its background in two and a half minutes. Very roughly, mind, but it’s still a hell of a lot better than saying ‘birds are dinosaurs’ and expecting the public to accept it. Anyone who says, “Well, actually, birds are dinosaurs,” and doesn’t at least try to fill out the background needs to do better. Sorry, rant over.

You can see though how the intro informed the structure of the whole video. I knew I had to cover the science, the history of the science, and the societal dynamics of the science to fulfil my promise of explaining what killed the dinosaurs.

Part I, like the intro, flowed readily onto the page. Part II was also blissful to write. Half the video written in four days! Well, I thought it was half at the time…

I struggled a fair bit with Part III. Ironic when it spans a mere fourteen years to Part II’s two hundred, but there’s just so much to cover. I started writing it chronologically with the Alvarez paper, then hit a roadblock as the meat of the debates began. How would I group events? What happens when? What would I cut? A top ten list was, in the end, the most efficient approach, though it genuinely pained me to frame the whole thing with such a trite format.

Then came Part IV. Oh, Part IV.

In retrospect, shoving an analysis of science in the media, the history of the debates from 1994 to 2023, and an overview of communication models into one section was a mistake. While Part III was packed, it was at least one concept.

My one stroke of good luck was that I was about to include examples of Goldacre’s wacky, scare and breakthrough news stories for the K-Pg extinction without realising. When I noticed, I was so relieved to have a coherent structure for at least the first half of the chapter that I wasn’t even mad Goldacre’s depressing vision of science media was right. The second half of Part IV though remains rather scattershot. ‘Anyway, can we talk about dinosaurs again?’ is my own internal monologue writing that line.

Part V originally existed as a subsection of Part IV, but as the script developed, I realised an examination of my own biases deserved its own chapter.

For obvious reasons, it was a nightmare to write. It felt like every point I tried making was instantly undermined by the very subjectivity I was putting in focus. Plus, would people accept an enormous left turn into my own backstory when they’d come for dinosaurs? How could I possibly make a good ending out of that? I felt deeply that Part V was necessary – how could I ignore the fact I’m providing just as biased a viewpoint as everyone I criticised? – but it was painful to see it through. I’ll speak more about this in a bit.

Somehow, after many more weeks than planned, I came to the end of my script. I spent another week or two editing that script and, despite trying my best to cut and not add, found an extra twenty minutes. Typical.

The script took one full day and a bit to record. If you listen closely, you can hear my voice getting hoarser as the video goes on.

I began editing the video at the start of May, and it turned out to be one of the most soul-crushing things I’ve ever done.

I would finish a full day at my actual job, then spend six or seven more hours driving myself crazy shuffling audio around and trying not to break my PC with the animation strain I asked of it, day after day for weeks on end. At one point, I spent three entire days – a weekend and a bank holiday – battling a 3D animation of one of the extinction hypotheses, only to realise at the end that I’d completed less than three minutes. Thirty or so hours for three minutes. The 3D animations are decent, but they aren’t good enough to justify that time investment.

I almost always hate my videos towards the end of the production process, but this was another level. Other than a few days meeting friends or family, working on it and procrastinating work on it stole all of May and June from me. I hoped it would be cathartic to write that, but I’m just angry now.

Here’s a fun example of how bad it got. There’s a twelve-second shot in Part V where a load of survey answers flash past in the lead up to ‘doesn’t matter’. I spent six hours figuring out the best way to do it, deciding the least worst way was recording a VBA macro in Excel, and learning just enough VBA to implement it.

Since I’m embracing the unhinged soapbox now (sorry, I’ll get less angry once I’m done), let me recount the ordeal I went through after all that to render and publish.

After sixteen hours of overnight rendering, my PC crashed. The output file was corrupt and all I could recover was a silent, sped-up, data-moshed version of the video. I tried to find an earlier version of the file in my online backup and discovered my online backup hadn’t been working for three years. Don’t mix OneDrive and Backblaze, kids. I panicked, decided I wasn’t comfortable continuing without some kind of recovery option, and copied everything to a newly bought physical drive instead of pressing forward with the video. That was quite the weekend.

I decided to render each chapter separately, then combine. Another sixteen hours for the first pass, then substantially less for the master as it was re-exporting a mash-up of the already rendered chapters. I gave the draft to my Discord reviewers and decided to only mess with the master from then on for the sake of time and sanity.

I also reviewed the video myself, combining my list with those of my awesome Discord helpers to end up with 180 tiny tweaks that had, in my opinion, a significant positive effect. Incredible the difference a quarter of a second’s pause here and there makes.

I thought it was done. I rendered, uploaded, set the premiere, and sat back to watch with my subscribers. But this video wouldn’t be this video without a final sting in the tail.

In making the many tweaks, I’d accidentally copied a single line of dialogue over the top of another. I only found out an hour and a half into the premiere. Cursing YouTube’s lack of a proper editor for uploaded videos and failing to get any good sleep that night, I fixed the error, re-rendered again, watched the whole thing to make doubly sure I hadn’t let any other problems slip in, and released the final, absolutely done, I-don’t-want-to-even-think-about-this-video-ever-again version at 5am.

It’s a matter of great personal pride that I went to work the following morning and managed a solid day in spite of the stress and sleep deprivation. I don’t have a clue how.

Omissions

There’s a comment on my video (that I annoyingly can’t seem to find) which praises it for an unshakeable dedication to scientific truth, or something to that effect. That comment is wrong and I’d like to correct it here.

As stated in the video, I made it for entertainment, both for myself and my viewers. I could well have delved much deeper into every scientific question, but suggesting such an approach ignores the other requirements of documentary-making. I had to make something entertaining, succinct, meaningful, etc., and I had to make it in finite time. All these constraints take time and effort away from understanding the science and sociology, and none are in any way an expression of pure scientific inquiry.

This video from the director of Shazam on the problem-solving of filmmaking is a better reflection of what I’m trying to say than anything I could write.

In short, I could not and can never cover all the science, even all the science I read. I accepted that most of my research notes would go unused early in the script-writing process. But for those interested, I thought I’d list here a few of the more interesting titbits I had to cut. There were, of course, many more that didn’t even make this list because I reached my mental limit with this article.

The Big Other Four

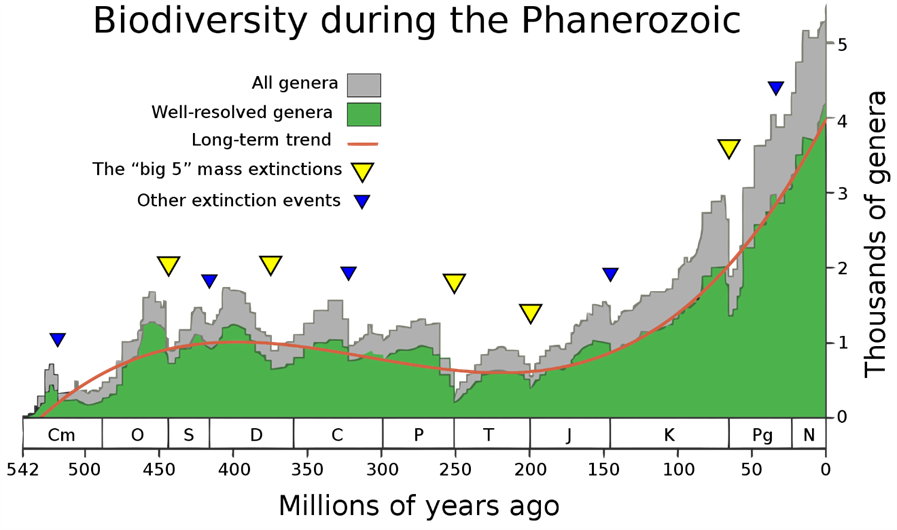

The K-Pg mass extinction is one of the “Big Five” mass extinctions in the Earth’s history. While there are many other notable extinction events, these five stand out as particularly severe for animal life on this planet. See the yellow arrows on the diagram below (from Wikipedia).

Each has prompted its own flurry of angry back-and-forth across scientific disciplines about extinction methods which is why I skipped the topic, though the K-Pg debate was always going to be the most explosive thanks to the ever-charismatic dinosaurs.

From my sources, here’s the current state of understanding for the “Big Other Four”:

- The Ordovician-Silurian event (first yellow arrow) is most often seen as a result of global cooling and glaciation, perhaps brought about by continental drift. Others contend volcanoes were involved. Mass media frequently claims it was a gamma ray burst from a nearby supernova, but this has little support in scientific circles.

- The late Devonian event (second yellow arrow) is probably the mass extinction we understand least. I haven’t read enough to put forward a summary with any confidence, but I do know it was the first extinction to have a paleontologically sophisticated argument for asteroid impact proposed. Digby McLaren gave evidence that it might have been a comet cluster at a conference in 1970, but he failed to ignite the mass extinction debates ten years ahead of schedule since he killed off some boring fish and nobody cared.

- The Permian-Triassic event (third yellow arrow) is the most severe extinction event animal life has ever faced. Somewhere around 95% of species disappeared. The consensus – which only became consensus in the 2000s – is flood basalt volcanism in Siberia. Opponents of the K-Pg asteroid hypothesis cite this as a reason to support Deccan volcanism for that extinction, but Siberian volcanism in the end Permian was significantly more intense. We also have solid evidence for stepped extinctions that match a feedback loop driven by volcanoes.

- The Triassic-Jurassic event (fourth yellow arrow) is quite confidently blamed on volcanism. Specifically, the rift volcanoes that broke Pangaea apart and formed the Atlantic.

One other notable extinction was the Oxygen Catastrophe, which took place 2.5 billion years ago. In terms of number of species of anything killed, it probably exceeds even the Permian-Triassic event, but it affected microbes and predated the evolution of animals so isn’t included in the Big Five. We’re confident the cause was photosynthetic bacteria pumping enormous quantities of oxygen into the atmosphere, oxygen being poisonous to most life that had evolved up to that point.

The Ultraviolet Theory

A few days before the Alvarez paper, a theory appeared which claimed dinosaurs went extinct due to chlorine in the atmosphere destroying ozone and letting in harmful ultraviolet light. I mention this theory because it claimed the reason the survivors survived is that they had fur or feathers to protect them while dinosaurs didn’t.

Few things highlight just how much our understanding of dinosaurs has changed since 1980 than a theory claiming dinosaurs went extinct because they lacked feathers.

Asteroid Tracking

Whatever you think of the justification, the mass extinction debates spurred public and governmental interest in asteroids. Luis Alvarez himself publicly warned Americans about the danger they faced in the early 1980s, and thus Congress asked NASA to make a concerted effort to understand local asteroid threats.

There’s a curious chapter in The Mass-Extinction Debates written by S. V. M. Clube, then Senior Research Fellow in Astrophysics at Oxford. Clube compares the asteroid threat to an unseen devil ready to exact Biblical cataclysm, which isn’t a unique perspective, but the sheer theatricality of his descriptions unsettled me. His frequent use of ‘demon’ to mean asteroid in particular rubbed me the wrong way.

I realised soon after that this reaction might be a product of my privileged 2023 mindset. The resources NASA and other agencies have poured into asteroid tracking in recent decades mean we’re now confident no Chicxulub-sized asteroids will pay us a visit any time soon. Smaller asteroids – city killers – could still lie undetected, but we’ve pretty much ruled out impending extinction by space rock.

I remember hearing a statistic that the world has collectively spent only a third of Wayne Rooney’s annual salary on asteroid defence, but I checked and, even assuming Rooney’s peak salary, this isn’t true anymore. Such a shame, since I was planning to make a joke about how we should be spending that kind of money watching the lumps of rock that actually matter.

Issues With the Fossil Record

I mentioned difficulties interpreting the fossil record a few times in the video, but this in itself is a gigantic rabbit hole I skipped over. I’ll cover a few snippets here.

The only reliable fossil record we have for dinosaurs leading up to the K-Pg boundary comes from Hell Creek in Montana, US. Is our understanding of biodiversity trends in the late Cretaceous biased by such an incomplete picture? An awful lot of work has gone into answering this question, and the best summary I can give is: yes, but we’ve found ways to correct for the bias. Most of the remaining uncertainty about Chicxulub vs Deccan comes down to gaps and dating problems like these.

Occasionally a news story pops up claiming palaeontologists have found fossils of non-avian dinosaurs that survived the K-Pg mass extinction. These are quietly and invariably debunked a few years afterwards when further analysis confirms such fossils were “reworked” into Palaeocene rock. That is, they were dug up by some geological process millions of years after being buried and re-buried in new rock.

In 1982, palaeontologists Philip Signor and Jere Lipps described the Signor-Lipps effect. This explains why mass extinctions are often so hard to conclusively point to in the fossil record, especially for scarce animal groups. It swayed a fair few vertebrate palaeontologists away from their stance that no mass extinction had occurred at the K-Pg boundary, and multiple studies since have confirmed that new fossil discoveries fill in the gaps as predicted by the model.

Nyquist’s Theorem for Geology

Nyquist’s Theorem is a mathematical result which constrains the minimum sample rate needed to achieve a certain resolution for periodic signals. It’s integral to audio recording and processing.

It turns out there’s kind of a geological analogue (heh, analogue). Sedimentation rate varies by environmental conditions, and since sedimentation rate is basically the resolution of geological time at a location, you can’t identify rapid events – in audio terms, you can’t reconstruct high frequencies – if the sedimentation/sample rate is too low.

Deep sea sediment is laid down very slowly for instance, so it’s a poor indicator for quick events such as an asteroid impact. You need a certain fidelity to see closer, and sediment laid down quickly enough to have high enough fidelity is hard to find.

Exacerbating Factors of the Chicxulub Impact

Anti-impactors might point to the fact we’ve seen plenty of big asteroids hit the Earth throughout history and not all are linked to extinction events. Much research has gone into teasing out exactly why Chicxulub was so devastating.

One reason might be the unusual density of hydrocarbons in the ground that the asteroid hit. A whole lot of oil was incinerated or thrown into the upper atmosphere, multiplying the cooling and warming effects that followed. News headlines commonly sensationalise this by saying that if the asteroid had hit a few minutes later, and thus struck somewhere else due to Earth’s rotation, the extinction might never have happened. It might well be true.

Asteroids Causing Volcanoes

I’m a bit perplexed as to why so many seem to think this is an omission. At 1:13:08, I state that there is ongoing research into whether the Chicxulub impact could have affected the Deccan Traps. Admittedly it’s only two sentences and in retrospect I regret not going into more detail, but it’s there. Some commenters seem to have missed it.

While it might appear obvious that a gigantic asteroid impact would set off volcanic chains around the world – especially in the rough antipodean location of the Deccan – mantle plumes are complex structures woven deeply into the structure of the Earth. It’s a big ask for even Chicxulub to have wide-reaching effects beyond the crust.

In the last decade, scientists have studied the possibility further and have found tantalising evidence. I decided against emphasising this in the video as this so far seems too recent to have wide support.

Glen’s Longitudinal Study

William Glen makes multiple references to a longitudinal study on the behaviour of scientists during the arguments over K-Pg. This study informed his observations in The Mass-Extinction Debates.

Glen also says (in 1994, 1998 and sometime in the 2000s) that the study isn’t over and that he is/was planning to write an even longer book about its ultimate outcome. Unfortunately, I can’t find this book or the study’s conclusion. Is it still going? Has it been dropped? There’s no indication anywhere online.

Dinosaurs in Children’s Media

In her chapter in The Mass-Extinction Debates, Elisabeth Clemens asks: who cares about dinosaurs? Why do scientists and the public care so much about dinosaurs in particular?

She says many esteemed palaeontologists, including Bob Bakker, claim to have been inspired by books, magazines and natural history museums fostering their love for dinosaurs at an early age. Museums in particular want to have the biggest spectacle possible, so they turn to the biggest creatures. Everyone is inspired by dinosaurs, it seems.

It’s therefore hilariously ironic that she seems so disappointed with A Boy Wants a Dinosaur back in 1994, my own entry point to palaeontology circa 2000. To quote my research notes again:

HOLY MASSOSPONDYLUS BALLS THERE’S LITERALLY A REFERENCE TO ‘A BOY WANTS A DINOSAUR’ IN THIS META-ANALYSIS OF SCIENTIFIC DEBATE YOU HAVE TO MENTION THIS OR YOUR WHOLE LIFE HAS BEEN A WASTE.

Me, in a state of obvious panic

I initially hoped to dive deeper into my dinosaur inspiration in Part V, but cut it as it failed to make any good points. Nonetheless, I tracked down all the dinosaur books from my youth I still owned to see what they made of the extinction. I had to limit my search to non-fiction books as otherwise half the list would have been Astrosaurs.

In the end, the statistics of extinction mechanisms they mention are a bit muddled, so I dropped that analysis. I did find something else interesting though.

Out of 25 factual books on palaeontology I still own, from books for toddlers to the sources I used for this video, 10 were written by or had consultation from Michael J. Benton. Combined with the fact he was the main consultant for Walking With Dinosaurs, I think it’s fair to say no other individual has had such a significant direct impact on my own perception of prehistory.

Inductive vs Deductive Science

One of my favourites chapters in The Mass-Extinction Debates is Digby McLaren’s comparison of inductive and deductive science. To simplify:

- Reasoning deductively means starting with a known scientific principle and using it to explain new data.

- Reasoning inductively means starting with the data and working backwards to find the explanation, irrespective of established theory.

McLaren highlights how insistence on deductive reasoning has held back geology and palaeontology on many occasions throughout history, extending the lifetime of outdated paradigms. Lyell’s pure uniformitarianism is the obvious one for those who’ve watched my video, but there were many others. Kelvin’s estimate for the age of the Earth, resistance to continental drift, etc.

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is an extreme example of the opposite. Darwin looked at the data he’d collected and concluded, against his own will, that only a radically new theory could explain it. He found the implications distressing but nonetheless had to accept the evidence instead of perpetuating a paradigm that was no longer tenable. He expected pushback from theologians, but was shocked by those in the sciences who claimed his data-first approach was unscientific.

McLaren argues that empirical fields tend to switch from inductive creation of theories to deductive defence of those theories once established. That is, everyone soon accepts the theory and uses that theory as the assumed starting point for an explanation for everything. As I tried to stress in my video, this is only rarely indicative of a flawed paradigm, but it is thought-provoking.

Second-Order Assessment of Scientific Claims

How can the public assess the validity of the scientific claims they hear?

I found a fascinating article on the topic by George Kwasi Barimah, who explains why he disagrees with another researcher’s answer to the question. Either way, the answer appears to boil down to understanding valid scientific process when understanding the science itself is too difficult, i.e. interpreting the accuracy of the science by how “scientific” the authority presenting it acts.

- Is the “scientific authority” actually an expert? How far up the chain of education do they lie? I found it funny and a little bit depressing that, in the hierarchy of scientific expertise described here from (a) (lowest) to (h) (highest), I would only ever be at most a (b), and even then only in mathematics.

- Does the authority have a track record of honesty?

- Is the authority “epistemically responsible”? That is, do they respond to objections and abandon debunked ideas? Or do they keep parroting the same tired points in an increasingly dogmatic manner?

- Does the authority’s claim align with other scientists’ consensus?

The trouble is that these are all pretty hard for laypeople to assess. You aren’t going to go out and read multiple reviews to determine what the consensus is, are you? You’ll just take someone’s word for it.

The conclusion of Barimah’s paper is that those presenting scientific information should carry more of the burden of making their scientific validity assessable by laypeople. They should supply as much information as possible to help non-experts make an informed decision. Whether that will convince the bad actors is…easy to guess. But it certainly convinced me, which is why I added a lengthy analysis of my own biases to an already overly long video.

Comprehensiveness

Well, I’ve told you everyone’s opinions on everything ever. The truth is in there somewhere. Good luck finding it! What, did you expect me to help you?

Comprehensiveness is a common pitfall of science reporting. Rather than assessing the validity of competing claims, many news stories will present everything and expect the reader to decide for themselves. The motivation is admirable, but it leads to big problems.

Take climate change. There’s a clear and established scientific consensus that humans are driving global warming. But there will always be voices in and out of science claiming otherwise. Should the media present both sides or put some actual effort in and determine the trustworthiness of the claims they parrot?

In light of this, I decided my video should come to the same conclusion as the consensus on the K-Pg extinction. I may have presented both the impact and volcanism hypotheses, but I made it clear that asteroid is preferred in modern palaeontology.

Or at least, I thought I made it clear. Many comments have come to the “obvious” conclusion that it was both. Again, admirable desire for balance and compromise, but not in line with the reviews I read.

I don’t think I was successful in my aim here.

Scientists vs Science Mediators

The line between scientist and science mediator is blurry and this blurriness has varied across time.

Science communicators have been in the public eye longer than ‘scientist’ as a term has existed. In the 19th century, most scientists saw popularisation as part of their job – I may have been a bit unfair on Darwin and Owen to claim that they were engaging in ‘scientific subversion by means of public support’, because that was expected at the time.

As the 20th century dawned though, scientific fields became more specialised, so scientists had less time to spend on public outreach and more complex science to explain when they did. This is arguably what drove acceptance of the deficit model as the default approach to science communication. Scientists were simply too busy and the science too complicated to have a direct link from science to the public.

This ‘boundary work’ (as Elisabeth Clemens calls it) had the side effect of making scientists believe they were above the public, too important to get involved with all that noise and nonsense that journalists spout. This snobbery persists today – many scientists view science mediation as trivial or ostracise their colleagues who engage in it.

There are contradictory narratives about when this dynamic shifted – or was this interpretation ever actually correct? – but either way, today we find scientists at the cutting edge of research engaging directly with public outreach. Many of the sources I relied on for this video are popular science books written by experts, and I feel comfortable trusting and learning from them despite the generally derogatory view towards popular science that’s emerged over the centuries.

One interpretation is that scientists are trying to extend their control over how the public receive their discoveries. The idea is not to prevent deviations (in the language of the continuum model), but to have better personal control over them when they happen.

Competing Communication Needs

As I stated in the beginning of this section on omissions, I had plenty of other needs alongside the need to accurately convey the science. Both you and I should remember at all times that I’m taking the role of the journalist here, so all criticisms of media I’ve covered apply to me as well.

It turns out there have been studies into the competing communication styles of scientists and journalists, with some interesting findings. There are, I’m told, several distinguishing aspects:

- Scientists prefer serious, cautious styles focused on their own narrow subfield. Journalists prefer overviews, clear messages, and entertainment.

- Scientists expect journalists to serve them and promote their scientific goals, in the extreme simply quoting their own words at the public and nothing else. Journalists though hope to remain objective by maintaining distance from the scientists.

- Both scientists and journalists think they should be the camp in control of the narratives formed. When a journalist misrepresents a scientific field, the scientist might regard this as a step outside journalism’s remit to merely report their science, but a journalist would reject the scientist’s criticism as censorship from a biased party.

A lot of the issues Goldacre covers in Bad Science result from this disparity in communication needs. For instance, journalists often see themselves as translators, removing complexities and subtleties or exaggerating scientific claims to make something more interesting. In the context of prioritising the appeal of science, this makes perfect sense, but in the scientist’s context of prioritising accurate information, it doesn’t.

It’s been shown, for example, that journalists often have a story outline in mind before they contact experts. The experts can usually tell if a reporter is after one fact or quote rather than the expert’s view of the entire issue. I certainly fell foul of this while making the video – the plan I’d formed after reading a few sources instinctively put me off contacting experts directly out of fear they’d advise me to go down a different path. I only properly realised this after I’d written the whole script. By that point, the sunk cost fallacy was too powerful to challenge.

Speaking of how my own communication style contrasts a proper scientific mindset, let’s talk about all the jokes.

I’m part of the Horrible Histories generation. Spoof and hijinks have always been central to my consumption of factual information and they’re incredibly fun to produce (it doesn’t hurt that they play well with YouTube’s core demographics too).

It bothered me a lot though that I was taking considerable amounts of historical information and turning it into silliness. What would the experts I’d referenced think? Was I adapting The Mass-Extinction Debates – a serious and well-respected scientist’s life’s work – into a comedy? This anxiety definitely shows in a few places in the video and I don’t have a defence besides the points already mentioned there.

I can only hope the intellectual value stays with people longer than the jokes do. The response so far suggests viewers have taken my serious messages to heart despite the shroud of mockery (more on this below).

Reception

So, how did my attempt at a scientific epic go down?

Well, first off, I wasn’t expecting half a million views in three weeks.

My channel has hit its all-time peak in every metric since I published the video, orders of magnitude greater than anything I’ve created before. The evidence is undeniable: people love dinosaurs.

More than the view count though, I’ve been floored by the appreciation many have shown in the comments. Clear enthusiastic engagement with the humour, science, and messages. I even got an email from a researcher involved in one of the reviews I drew from thanking me for exploring the subject with nuance, which did a lot to quell my fears about how I might have trivialised things. Thank you to everyone for the kind words.

Is it gratifying to see this response after all the work I put in? Indeed.

I have a sneaky theory about why this video received such a warm reaction, one that supports the very conclusion the video reached. Although the animations, music, timing, etc. certainly contributed, I think I know the true reason why the video seemed to resonate with people, why they found it a compelling and poignant story:

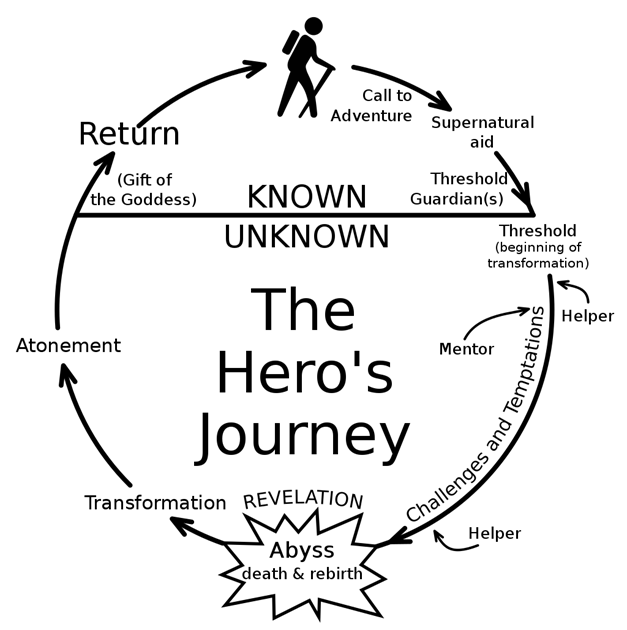

This video follows the hero’s journey.

I love adding unnecessary jokes to a video’s structure. This one begins with a chapter titled ‘The End’ and (if you watch past the credits) ends with the word ‘begin’. It’s also technically a two-hour-long your Mum joke, hopefully breaking a record somewhere.

But I’m most proud that a video about the all-encompassing power of narratives abides by the posterchild for all-encompassing narratives. No one noticed. I didn’t even notice – only while editing the script did I pick up on how I’d kind of stuck to it, and I decided to tweak a few things to make that structure more pronounced.

The hero’s journey, for those unaware, is a theory which states the majority of stories throughout history follow the same basic structure. The theory’s accuracy is heavily debated, but the influence it has had on storytelling philosophy has been colossal.

Not convinced? Here’s how I think my video lines up:

- Known world – A world where an asteroid impact killed the dinosaurs.

- Unknown world – The messy, confusing tangle of science and its processes.

- Call to adventure – Realising that even the question ‘What killed the dinosaurs?’ is incomplete in the intro.

- Supernatural aid – Visiting the Natural History Museum.

- Threshold guardian – Google and its insistence that an asteroid killed the dinosaurs, I guess. This one’s a bit fuzzy.

- Crossing the threshold – Transition to Part II, beginning to dig into the history of the question.

- Challenges and temptations – All the fun and games of Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

- Mentor – William Glen via The Mass-Extinction Debates.

- Helpers – Other sources explicitly mentioned that helped me on my journey, e.g. Ben Goldacre.

- Abyss – Falling off the cliff of scientific inconsistency at the end of Part IV. Is me staring into the gaping darkness too on the nose as a visual metaphor?

- Transformation – Realising I must examine my own place in the media landscape I was analysing.

- Atonement – Coming clean about my own biases.

- Return – Arriving back at the conclusion that an asteroid probably did kill the dinosaurs, but with the wider appreciation of the scientific ecosystem that led to the result.

- Gift of the goddess – A deeper understanding of scientific process that can be applied to other, more pressing questions.

Maybe I’m staring at my own navel a bit too much here, but I genuinely think viewers subconsciously picked up on the familiar story beats. I apparently did when writing it. My worry then is: did we all replace an accurate conclusion with the hollow affect of a satisfying conclusion provided by the hero’s journey? The meta is thicker than treacle right now.

Since we’re on the topic, then: what of my conclusion?

I went in circles for so long trying to figure it out. Yeah, ok, the video lied. I didn’t know the answer as soon as I had A Boy Wants a Dinosaur in my hand alongside The Mass-Extinction Debates. I knew there was an inkling of an answer in there, but the specifics eluded me.

I had to balance apparently competing beliefs that paradigms are dangerous (as in Mass-Extinction Debates) and that paradigms are trustworthy (as in Bad Science). As I said earlier, I knew it couldn’t just be a vague warning about paradigms as that would wrongly embolden the climate change deniers. It wouldn’t really challenge anyone’s beliefs.

My eventual answer came from deciding what all the failures of communication I’d covered had in common. Both the reluctance to abandon incorrect paradigms and the desire to fight against paradigms wrongly perceived to be incorrect are, in my view, products of storytelling. We all want to hold onto our established beliefs. We all want our oppressed beliefs to win out against a powerful empire of evil.

Is this a good conclusion? I’ll be honest, I don’t know. Again, the other constraints of filmmaking forced my hand. I’d gone in circles so long that I just wanted something sensible so I could get on with it. The message is the best I could get without spending even longer on it.

I’ve been told this conclusion is tired and unoriginal. Probably true, but I’d like to end this article with some reasons why I think it’s still important to emphasise.

There will always be people who dislike a YouTube video. I don’t have a thick skin, but I’ve accepted the reality of internet discourse over the years. The small but vocal contingent of assholes doesn’t bother me too much these days.

I mean, take this one.

I asserted that scientists are unwilling to change opinions because I read it in a book written by someone who’d performed a long-running study on the subject. I didn’t discredit Darwin, I just stated that even he is subject to the forces and fallacies of science discourse. And I used a great many sources, thank you very much. See, easy to debunk and move on. Well, the Pavlov’s memes point is probably accurate.

The problem for this video hasn’t been the comments that disagree with me. It’s the comments that agree with me and think my conclusion supports their fringe scientific beliefs.

Yes, even though half this video was an attempt to avoid it, I’ve ended up falling right into the trap of emboldening doubt about science as an institution. Well, sort of. Let me explain.

First things first: for transparency, my day job is working for a renewable energy company. I’m literally in the pocket of Big Green. Although I should emphasise, I went into that field because I accept the scientific consensus that anthropogenic climate change is real and dangerous, not the other way around.

It’s therefore greatly distressing to read a non-trivial number of comments like the following.

Wow, great video about science, man! So great to hear you agree with me that humans aren’t causing climate change!

There are several rebuttals I can think of here, all of which appeared in the video this person apparently watched. Expertise in one field does not translate to expertise in others. Everybody, educated people included, will jump to accusations of conspiracy if they feel threatened. Despite all the mess, the scientific method is self-correcting and has come to roughly correct answers more often than not.

But then again, I did also explain how we should live with uncertainty. I did explain how science can be held hostage by problematic consensus. I hoped I could avoid people twisting my words to make these their takeaways, but clearly not.

I’m not an expert in climate science. I have to use all the strategies outlined in the video and this article to assess the validity of scientific claims from authorities I can’t inherently trust. Do I even have the credentials to push back against comments like these?

My video presents many contradictions about science. If you accept death of the author, I suppose you can cherry-pick the parts that fit your perceived worldview and read it as supporting more scrutiny towards climate science. Equally, you can be blinkered to the nuance and see it as a wholehearted rallying cry for climate action (which, if I’m being honest, is what I hoped for).

This is why I believe my conclusion is important, a view that’s only strengthened as I’ve watched each comment come in. You need to reassess your bias towards closely-held narratives. Not the people you disagree with. You.

How forthcoming have the sources you’ve used been with their own bias? Where do they fit into the science ecosystem? Is the narrative in your mind a little too neat, or does it yearn a little too much for maverick dissenters? I’m going to be asking myself these questions a lot more from now on.

I’ve had a geologist in the comments tell me the other four of the Big Five mass extinctions were ‘without a doubt 100%’ volcanoes, then backtrack to ‘I probably shouldn’t say 100%’ when challenged. I’ve had a Creationist rant about how evolution – ‘evolutionary mythology’, as they put it – doesn’t exist. I’ve had an anti-vaxxer chastise me for stating that the MMR vaccine is safe in an ‘otherwise fantastic documentary’.

I think, once the dust settles, almost everyone is going to leave this video with the same beliefs as those they went in with.

…which, you have to admit, kind of proves my point.

Conclusion

I’m not going to fix science with one video. Not that I was trying, but I think I skirted a bit too close to that goal with my enormous scope. I boxed myself into a corner and got out by the skin of my teeth.

Maybe I was too harsh on the [REDACTED] article about the debates that got me so riled up. Commentating on crises in science and media is hard. I’m not sure I’m cut out for doing it again.

If there’s a conclusion to draw from this outpouring of random thoughts, it’s that there were many positives in making and presenting this video, but a lot of negatives too. My mental health has suffered a lot. For this reason, I’m giving YouTube a break for a while. Maybe a month, probably longer. I need to focus on my personal life and forget this crazy internet we live in.

Thanks again to everyone who watched, enjoyed, and engaged with The Mass Extinction Debates. You’ve made it worth it. Ultimately, I embarked on this project for no other reason than to prove to myself that I can do it, and the response has provided plenty of evidence that maybe I can.

And sorry to everyone who’s excitedly subscribed in the hope of new content just like it sometime soon. It might be a while.

I loved your Mass Extinction entry on YouTube. I thought I had fallen into a Monty Python skit. Brilliantly funny & insightful. I learned many things and laughed my ass off. I pressed the Submit button, but I don’t know if I’ve actually subscribed. I wasn’t asked for an id or anything. But then I got an e-mail from wordpress? All I really want is to see more Youtube stuff from you.

can I have access to the pie charts?

Sure, here they are:

https://oliverlugg.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Q1.png

https://oliverlugg.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Q2.png

I’ve also linked them in the article itself now, so thanks for reminding me I hadn’t.

Just wanted you to know your video might genuinely be in the running for my favorite videos this year, let alone paleontology associated. Its funny, precise, and now has to be the voice of a study that most laymen never heard of outside of oldees online.

I eagerly await your next video, whatever is and whenever it is.

If I have a question though; Now that the video is out in the wild, why don’t you talk to the Skeleton Crew or other online personalities associated with paleontology now? You have clearly made a name for yourself, and most paleontologists I have met have been truly appreciative of this complex and messy part of our history. So honestly, caping it off with an interview of a modern group of Paleontologists might bury this work for good and also could help make some new contacts in the field if you ever want to make another video in Paleontology again.

No matter the case, as someone who intends to become a paleontologist in college I can’t help but be thankful for your video and Red-Raptor-Writes reviews for bringing back my love of prehistoric Fauna I gave up on when Highschool got rough.

With appreciation, Kyo

Hi Kyo, thanks for the kind words!

I’m not familiar with the Skeleton Crew, though having looked them up it would be interesting to learn what they’d have to say about my video. I’ll consider reaching out to them, although at this point I’m moving on to other projects (most if not all non-palaeontology), so I don’t feel much need to extend the life of this one further, and I doubt I’d be as sharp with my knowledge of the area as I was a few months ago.

Haven’t watched it, know you from the diplomacy video and 5d chess

I *entirely* agree with your stance on the conclusion. To be fair, “work on yourself” is advice older than the bank of england, but it is the only good “antidote” to buying narratives to justify your existence to yourself, creating a healthy bit of paranoia about it.

This “interpreting reality” thing is both hard, confusing and tiresome.

All this is to say, kick ass work, and i should probably study more.

Only six comments on the follow up blog post, after such a marvelous video? For shame, internet!

On the original video I left a comment saying something like “as a geologist, I must compliment you on your dedication to scientific accuracy”. Reading this essay I realize now how much anguish that must have caused you, so I’ll use this forum to clarify what I was trying to communicate.

As an undergraduate (who thought he wanted to be a paleontologist), the extinction debates played a formative role in my development as a scientist. The Glen book was my first glimpse of the academic side of academia, and it would lead me to spend a great deal of my time in undergrad trying to understand what science means, how it works, and what people have though of it over the years. So saying: if I can compliment anything in your video, it’s the fact that you neatly captured the frustration that I was working through at the time, and would continue working through for the remainder of my degree and beyond.

You state in the documentary and this essay that an antimony you were seeking to suss out was a frustration between what science aims to be, and what science is practically. What this means is revealed to be something like the following: You understand science to be a system of rational inquiry into the world (perhaps opposed to religion), in the sense that it justifies its theses on the basis of observations and tests of the world. Given this, you feel that a sufficiently careful and intelligent person ought to be able to follow a scientific theory down the daisy chain that led to its creation, see the chain of reasoning, and then go on and do the same in other areas. In practice however, as soon as this reasonable person scratches the gossamer presented to the public a world of academic debate is revealed on almost any topic one can choose. And when a well intentioned individual tries to weigh in on how things look to them, the response is “YOU’RE NOT AN EXPERT”. If the person persists in both weighing in on academic topics, and in not being an expert, then they become a crank, like the (dozens? hundreds?) of commenters you bemoaned waiting in the wings to use your argument in their personal war against the scientific consensus.

Yet this is precisely what the media does routinely, and they’re upheld as truthseekers, standing up for the little man and holding power to account? How can the activity of one group of truthseekers be directly counterposed to a different group of truthseekers, if there truly is only one truth? It seems fanciful.

I’m glad I found this essay, because I feel that it provides closure to the issue you were truly concerned by. You very adroitly side-stepped the high profile, politically charged questions that stir the public up against scientists in the video – I’d show it to my family members, if I thought I could get them to agree to it for a movie night. Far more than any question about dinosaurs, asteroids or paleontology, I think you were attempting to understand your own place in this career you were building for yourself on youtube. What degree of questioning authority is acceptable, and where is the line in the sand drawn that gets you labelled a crank?

As other people have stated, you could make a solid career for yourself as a paleotuber. Even as a self-labelled non-paleontologist, you have made by far the most entertaining, intelligent, informative, and thoughtful video about the *science* of paleontology I’ve encountered on the platform. You admirably avoid naming names; I feel no such compunction behind my pseuonimity. if you want to see a much more typical example of the level the platform tends to sit at, look at PBS Eons. More-or-less mindless regurgitation of whatever headlines are making their way across reddits and the science outlets. You admitted to drawing inspiration from breadtubers; you’re funnier than most of them are these days to boot. You could easily pivot your entire channel to being about this kind of deep dive. Irreverent, in-depth analyses of science and the people who do it, the legacy we inherit from it. As you go on, maybe take some shots at the more unsavoury, problematic figures in its past, sighing in relief that we’re past all THAT unpleasantness, but with the burdensome knowledge that we have so far to go still… and at the end of the video, you always come back to the same conclusion: at the end of the day, how do ANY of us really know what’s going on? Science is the best we can do, and scientists are doing the best they can – and none of the rest of us can really claim to be doing any better. Cue brick joke, running gag, thank patreon, roll credits, the end. If that sounds appealing to you I think you ought to do it. You’d do it well and be better at it than most of the people running the game now.

I sense in your writing tone a deeper frustration yet. I can’t say quite what it is, but I suppose it must be amazement that it worked exactly how you thought it needed to and would, and yet nothing changed. As you said, nobody came away with their ideas or mind changed. Only someone who wants his or her mind changed, is able to allow it to be changed. For everyone else, it will always be merely Content. You seem to have the creative streak which many STEMists in this day and age don’t quite get stimulated by in their profession.

A wise man once said Art in the modern age: you can either produce something that’s so broadly appealing and bog boring it has mass appeal, or you can do something so well that a small group who really wants it has to come to you for that thing. You said you have 26,000+19,000+2 books worth of information? Between those sources, plus some of the ideas in jefferson mammoth cheese, this writeup, and the comments responses you’ve made, I bet you have a publishable book. Of course, you may not be able to stomach a return to this topic just yet. But I put it to you that at some point you’ll have to make the decision: do you want to be the big fish in the small pond you were certain you could be? Or do you want to genuinely attempt to engage with people who are interested in the kinds of ideas that you’re interested in pursuing? The book suggestion is really just something that, as an outsider, appears as an available option, an uninformed peanut thrown from the gallery.

I’m quite certain that you already have other ideas in mind.